Imagine a world without elk, deer, wild turkeys and other game animals. What would you do on the weekends? How sad would it be to drive around without seeing wild animals in the fields and forests? How much would you miss fresh wild game on the dinner table?

To a hunter, it’s a devastating thought. That’s why, since the late 1800s, hunters have taken it upon themselves to support wildlife conservation and follow sound management practices to protect and preserve wildlife and wild places. Today, wildlife populations are plentiful and flourishing, but it wasn’t always that way, and some of the darkest days for wildlife weren’t all that long ago. Let’s take a closer look at the history of wildlife conservation, and the efforts made by hunters and conservationists to ensure animals had—and will continue to have—ample land and opportunity to persevere.

Robert D. Brown, dean of the North Carolina State University College of Natural Resources, published a paperand created a timeline to overview the decimation of numerous wildlife populations. In the 1500s and 1600s, Native Americans inhabited what is now the United States. “It is thought that they hunted mammals for food but that they decimated large game around their population centers and crops,” Brown said. When European immigrants arrived with infectious diseases, many Native American populations suffered and perished. The immigrants also killed the natives over land disputes and other conflicts. Native Americans also fought to survive through long droughts, severe winters and other changes to their environment. As a result of the diminished Native American population, wildlife populations started to rebound where they were locally depleted, but not for long.

The Europeans cleared land for farming, cut trees for shipbuilding, and began hunting and trapping for European commercial markets. Habitat was lost, and hunting and trapping were unregulated, which negatively affected wildlife populations.

As people expanded westward across the continent, they found new opportunities. Lewis and Clark toured the West from 1803 to 1806 and made detailed observations of the West’s natural resources and geography. Bison herds were plentiful, with an estimated 30 to 75 million animals, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Lewis and Clark’s notes said the abundance of wildlife exceeded anything they’d ever seen. That, too, quickly changed as people moved west for the California gold rush of 1849 and as the railroad expanded in the 1860s. The bison population declined by millions.

Market hunters killed animals to sell meat and hides, and that led to the exploitation of natural resources for profit. With little to no oversight, bison were slaughtered to near extinction. It’s believed that only 300 wild animals were left in the U.S. and Canada, according to the USFWS webpage. Other animals, including beavers, deer, turkeys, wood ducks and passenger pigeons also decreased in numbers.

In the 1800s, people began to see a need to better conserve our natural resources. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s historical timeline explains that “by the mid-19th century, Americans began to realize that unrestricted killing of wildlife for food, fashion and commerce was destroying irreplaceable resources.” Iconic figures like Theodore Roosevelt, John Muir and Aldo Leopold started speaking up and creating clubs, programs and eventually laws that protected wildlife and wild places. The conservation movement caught momentum and led to the many changes and protocols we see today. These laws helped develop the seven principals for the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, which state wildlife agencies and outdoor industry members use to guide wildlife management and conservation decisions.

1871: Congress created the United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries to study the decrease in the nation’s food fishes and recommend ways to reverse it. The Commission was reorganized into the United States Bureau of Fisheries in 1903.

1872: Congress established Yellowstone National Park as the first national park in the world, consisting of nearly 3,500 square miles of land.

1896: The Division of Biological Survey was created under the Department of Agriculture from the 1895 Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy to map the geographical distribution of plants and animals in the U.S., as well as study the effect of birds in controlling agricultural pests.

1900: Congress passed the Lacey Act (the first federal law to protect game), making it illegal to trade protected wildlife. It also regulates the shipment of illegally taken fish, wildlife and plants.

1903: The first unit of what would become the National Wildlife Refuge System was established in Florida. It’s now called the Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge.

1916: The National Park Service, the federal agency responsible for the care of national parks, was established.

1929: Congress passed the Migratory Bird Conservation Act, which was the first step in protecting migratory birds. It established the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission to find and approve wetland areas to acquire with Migratory Bird Conservation funds. In 1934, Roosevelt signed the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act to stop wetland destruction. It also required waterfowl hunters to buy and carry a Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp, better known as the Federal Duck Stamp.

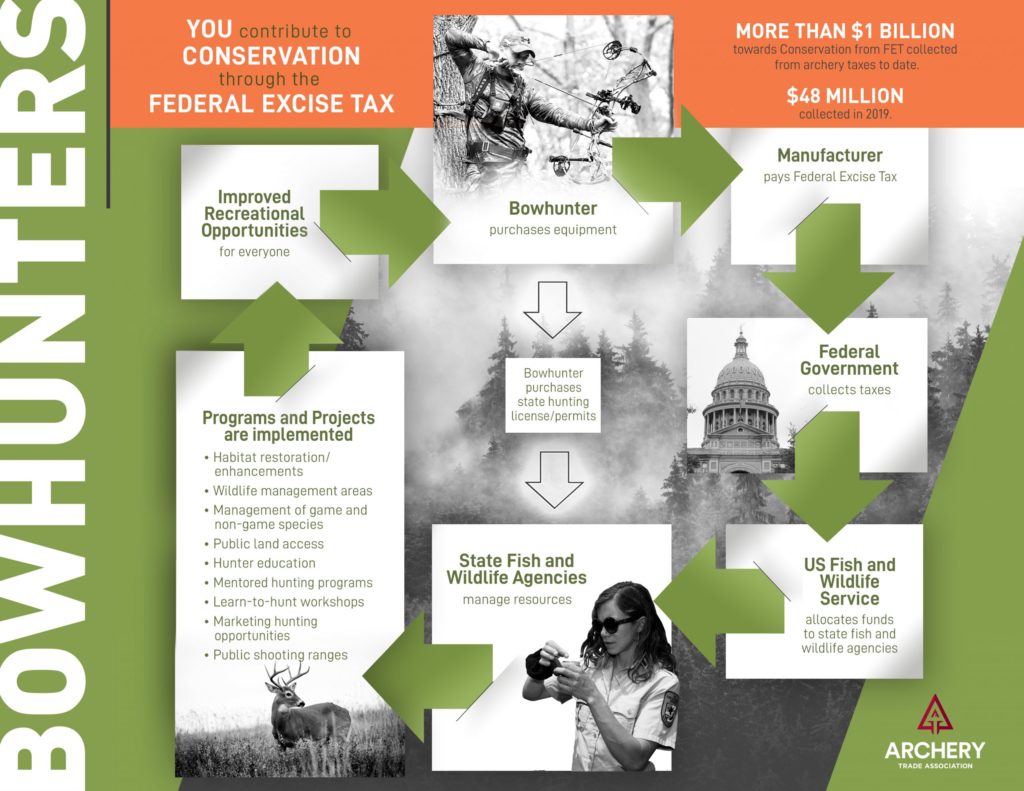

1937: Congress passed the Wildlife Restoration Act, aka Pittman-Robertson Act, which raises money for state wildlife agencies in the form of taxes on firearms, ammunition and hunting equipment. Archery equipment was taxed starting in 1972. State agencies use the funds to pay for high-priority conservation initiatives such as habitat restoration, restocking programs, hunter education programs, and public-land access and acquisitions. This was the first sustainable source of federal revenue for state wildlife management in America.

1940: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was created when the United States Bureau of Fisheries and the Division of Biological Survey were combined. The USFWS is responsible for managing fish, wildlife and their habitats across the nation.

1973: Congress passed the Endangered Species Act, which identifies and manages rare, threatened and endangered species.

1993: The National Biological Survey was created to identify species and habitats at risk of becoming threatened. The NBS was renamed the Biological Resources Division in 1996.

2000: Congress passed the State Wildlife Grants Program, formerly called the Conservation and Reinvestment Act. The legislation allocates funds to state wildlife agencies annually. The agencies must use the money for a comprehensive wildlife conservation plan designed to keep species of special conservation concern from becoming harmed, injured or destroyed.

2019: Congress passed the Modernizing the Pittman-Robertson Fund for Tomorrow’s Needs Act, aka the P-R Modernization Act, which allows state wildlife agencies to use P-R funds to promote hunting and boost hunter numbers through advertising and marketing. State agencies can also use P-R funds for recruitment, retention and reactivation (collectively known a R3 efforts) of hunters.

Hunting is regulated to protect—and support—wildlife populations. America’s thriving wildlife populations are evidence of the effectiveness of hunting as a conservation tool. Hunters also provide revenues to support state and federal wildlife management programs that control and manage wildlife populations. Over the years, hunters have generated millions of dollars for wildlife conservation. Better yet, they’ve happily paid for licenses too. Since the P-R Act passage in 1937, hunters have generated $19 billion for conservation, which is in addition to the $900 million generated from state licenses, tags and permits. Funds from archery equipment (which started being taxed in 1972 through the P-R Act) recently exceeded $1 billion. The Federal Duck Stamp has also generated more than $800 million since 1934, to fund more than 6 million acres of wetlands habitat.

So pat yourself on the back. Each time you hunt and tag a game animal, you’re helping keep wildlife numbers in balance with the habitat. And each time you buy a license and hunting equipment, you’re generating funds to ensure our natural resources will be available for generations to come.

Hunters are now deeply ingrained in conservation’s history as part of the solution, not the problem. But history is still being made. The choices you make today affect the future. Bowhunters must know their role in conservation and continually be good stewards of our natural resources, which includes following laws and regulations, following fair chase practices, making ethical shot decisions, cleaning up wild places, and supporting and volunteering for conservation organizations.