Many factors contribute to ethical bow-kills, including arrow weight, broadhead design, draw weight, draw length and shot placement. Of those, the most important is shot placement.

In Shot Placement 101, we discussed where to aim to make ethical harvests. This article discusses some of the tricky shot-placement scenarios bowhunters face. To help explain how to make these shots we interviewed Randy Ulmer, an accomplished bowhunter and former professional archer.

Steep angles from treestands require you to adjust your shot. Photo Credit: ATA

On flat ground, long shots are more challenging than short ones, but short shots get more challenging when adding elevation. Steep angles created by close shots from treestands require careful shot placement.

These situations can make aiming for the center of the lungs difficult. As the angle steepens, the exit hole gets lower in the chest cavity. At very steep angles, aiming at the center of the chest can cause your arrow to exit before striking both lungs.

“If they’re straight underneath me, I prefer they get a little bit out,” Ulmer said. “When you’re shooting straight down, it’s very easy to get just one lung, and more likely the deer will get away.”

Ulmer waits for the deer to walk far enough from the tree to reduce the angle, which ensures a double-lung hit.

Aiming for both lungs is the go-to shot placement for bowhunters. However, some situations make heart shots a better choice. Outdoor writer Bill Winke said a deer standing 30 yards away can drop roughly 15 inches by the time an arrow arrives while traveling 260 feet per second. If you aim at the center of the chest and the deer drops, you might miss or wound it. If you aim at the bottom of the heart in that situation, you’re much more likely to make a lethal shot.

When should you aim low?

“The older the deer and the more hunting pressure, the more likely it will jump the string,” Ulmer said. “If your area has lots of hunting pressure and you know deer typical react that way, aim a little low.”

Ulmer cautions, however, to never aim so low you could wound the animal if it doesn’t jump the string.

You can shoot a moving animal if you know exactly where to aim. Photo Credit: John Hafner

If an animal is walking by, come to full draw, aim and make a soft grunting sound to stop it. The noise usually makes the animal pause. The alternative is to take a walking shot, but only if it’s close.

“If a deer is under 20 yards and walking slowly, it’s a great shot because they typically won’t jump the string if they’re walking,” Ulmer said. “It takes an arrow a long time to go 20 yards. You don’t think so, but it does.”

When talking a walking shot, you must lead the animal a bit.

“If a deer is at 15 yards and walking slowly, I’ll lead 3 inches ahead of where I’d normally aim,” Ulmer said. “In that situation, aim right at the crease.”

It’s essential to differentiate shooting in your backyard from shooting in the woods. Adrenaline, elements and uneven footing are just some of bowhunting’s challenges. The stakes are much higher because bad shots have consequences in bowhunting.

Ulmer suggests taking the maximum distance at which you can consistently hit an 8-inch circle, and cut it in half for bowhunting. “If you can keep your arrows in an 8-inch group at 60 yards, your max in a hunting situation should be 30 yards,” Ulmer said

If your arrow grazes a branch or sapling, it can miss the target. How do you know if a branch will be in your arrow’s path?

“Let’s say you’re shooting at a deer at 40 yards,” Ulmer said. “Then let’s say there’s a branch at 20 yards. If you put your 40-yard pin on the animal, you can see where the branch is in relation to your 20-yard pin.”

The area at the top of the chest cavity will not produce a fatal shot, so this should be avoided if possible. Photo Credit: ATA

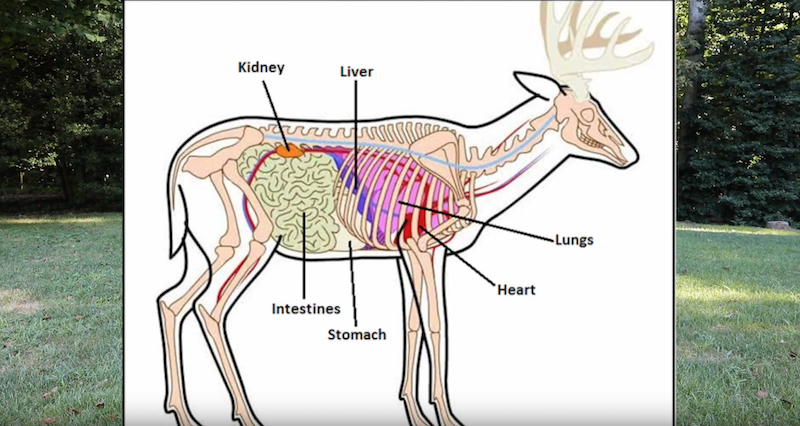

The area atop the deer’s chest cavity and below the spine is often called “no man’s land.” If an arrow hits there, you’ll usually find little blood to trail because it’s not a fatal hit.

The lungs and chest cavity go all the way to the spine, but it can seem like there’s a gap.

“If you shoot a deer just below the spine and a little back, you might not get pneumothorax (collapsed lungs),” Ulmer said. “There might be enough muscular tissue up high to seal the wound when the arrow goes through. If the wound seals, you get no pneumothorax. You’ll get little bleeding up there, too, so the deer won’t die by hemorrhage or by pneumothorax.”

When you finally get an animal standing within bow range, you’ll likely be tempted to rush the shot while worrying it will get away.

“Wait until you get a good shot,” Ulmer said. “People think the deer will get away, but you always have more time than you think.”

If it walks away, so be it. Close calls are much better than agonizing over a wounded deer.

Run through these scenarios while practicing your shot-placement and decision-making process. When your shooting opportunities arrive, you’ll be prepared for what to do.